by Colin Osman Hon FRPS

This article is based on the author’s illustrated lecture given at

the University of Bath on 15th March 1990.

I start with the assumption that we can learn from the past. It starts with the belief that if we are willing to look in detail at the problems faced by old-time photographers we will find it helpful when we pick up a camera to take pictures today. The fully automated camera with one-hour processing is a long way from the wet collodion process with its long exposures and the difficulty of preparing and developing a wet plate in a portable darkroom tent standing next to the camera. Amateurs only too often believe that a more expensive camera will enable them to take better photos when the truth is that it will only give them greater help in realising what is in their vision.

Consider first of all two photographers who stood before the walls of Peking in the latter half of the last century. Both used similar cameras and the cumbersome wet plate methods. One, Felice Beato, (Ref 1), was an experienced war photographer — the first in fact — and his boxes of glass plates and chemicals travelled with him. The second, in Peking ten years later, was Thomas Child (Ref 2) an amateur and a gas engineer resident in Peking and helping his finances with a sideline of supplying plates and chemicals to other amateurs, both Western and Chinese.

THE WAR CORRESPONDENT

The concept of the war correspondent was new. In the past wars their conduct had been the concern of generals and a very distant Parliament. Concern over the increasing public war expenditure encouraged a readership of newspapers and magazines wanting to know more and even questioning the wisdom of the generals. The Crimean War (March 1854- March 1856) saw the birth of the new profession of war correspondent.

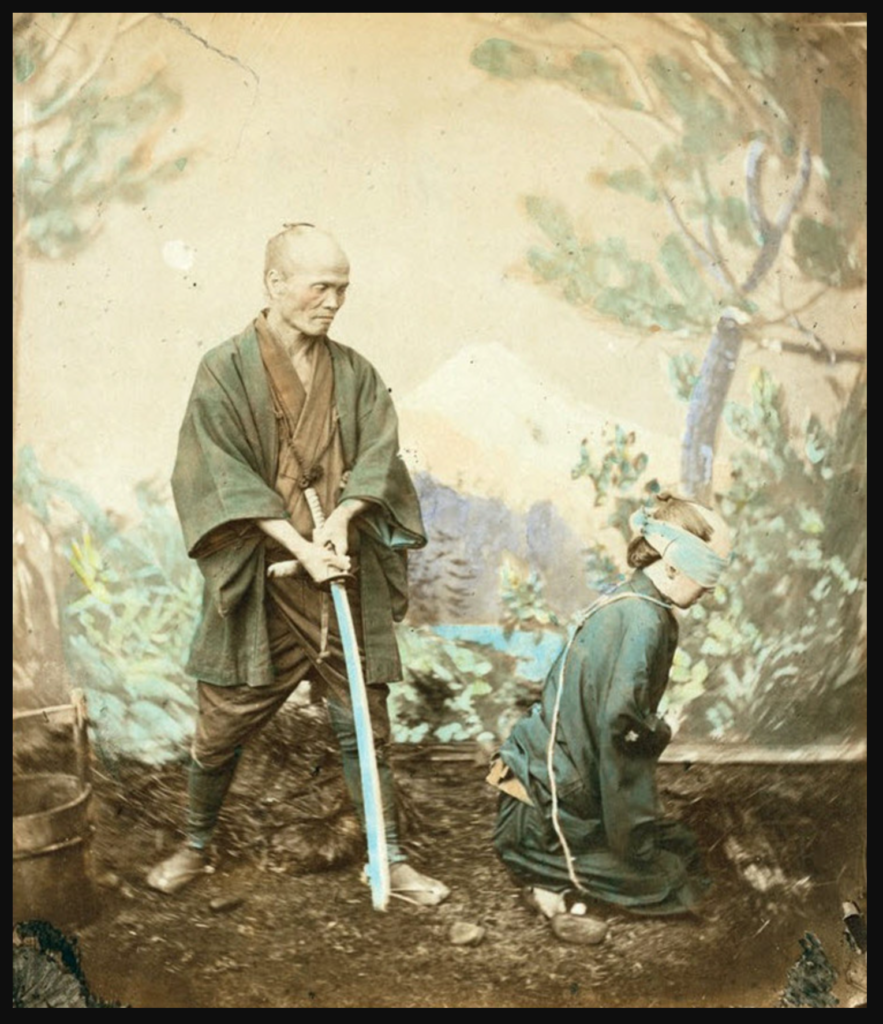

William Russell writing in The Times caused a sensation by telling the truth about the conduct of the war and earned the hostility of the military establishment. The artist William Simpson sketching for the Illustrated London News met with cooperation not only because he cleared all his drawings with the authorities before despatch but because it was almost impossible for a drawing to be critical even if Simpson had wanted it to be (Ref 3). The same applied to photographers Roger Fenton, James Robertson and to a lesser extent, Felice Beato. They could photograph the battlegrounds and even the dead but this did not raise any question of possible military blunders. Sharing the relatively luxurious officers’ quarters and travelling with the assistance of the officers perhaps it never even occurred to them that it would have been possible to photograph inside the dreadful hospitals made notorious by Florence Nightingale and exposed by Russell.

Felice Beato went on to the Indian Mutiny (1857-1858) and then to the Second Opium War (1857-1860), still enjoying the comforts and hardships of an officer’s life. When he stood with the invading army outside the walls of Peking it is hardly surprising that he photographed as he did.

Compare this with Thomas Child who finished his journey to Peking in 1870 not with a conquering army but as a terrified passenger alone in an almost open boat hauled up the river by coolies. He had come to run the private gas works of the Imperial Maritime Customs, a Chinese government department with an international staff. Unlike the diplomats everyone on the Customs staff was required to learn Chinese and in Child’s case it was even more essential as he had to direct his coolies to lay pipes and watch over his apparatus. He had taken this job to improve his lot as a gas-fitter for the Crystal Palace Gas Company. His working class background and his Methodist temperance upbringing gave him a very different view of the walls of Peking. He saw them as a resident not as a visitor and he probably saw them, as nearly as any Westerner could, as the Chinese saw them. The pictures show all this, the same walls through two pairs of eyes.

RISE OF PICTURE POST

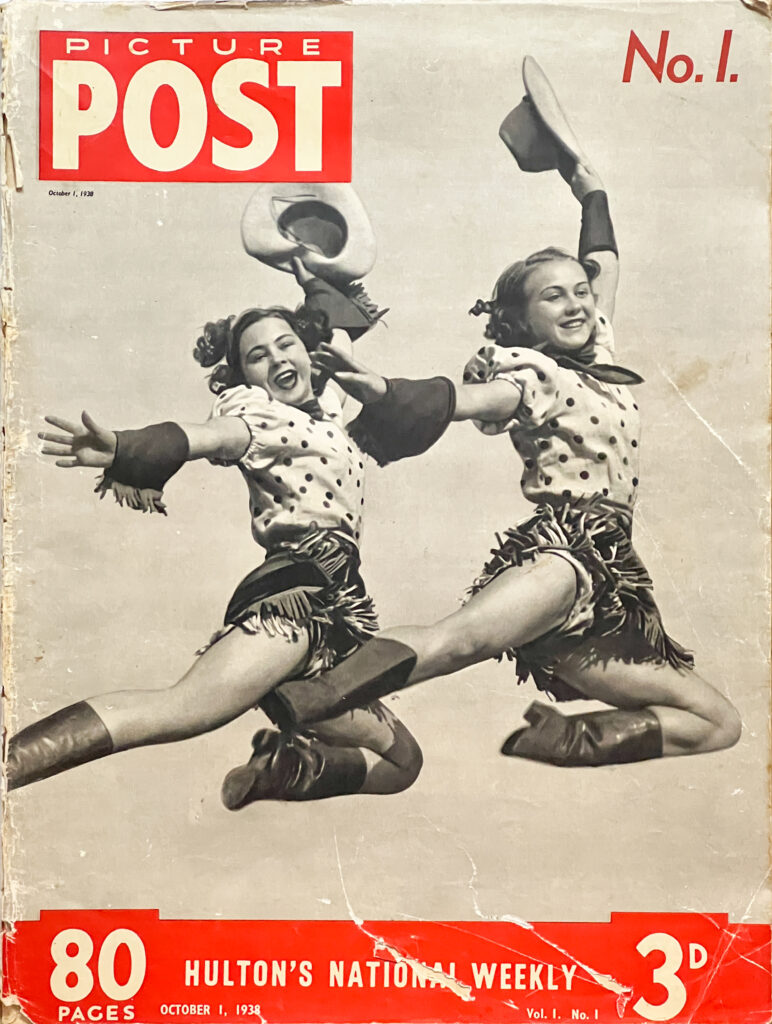

I want to move on more than half a century to another period where I have a little knowledge; the years 1938-39 and the founding of Picture Post. The story of its gigantic sales success is now a legend. On Day One of the magazine all the predictions were for disaster. The advertising agencies and the mighty W.H. Smith distributors virtually boycotted the new arrival and were singularly unimpressed by the dummy shown to them (Ref 4). What made this huge popular success? And how did photographers contribute?

First a few political notes. As every edition of Picture Post proclaimed the founder was Edward, later Sir Edward Hulton, who I think would be delighted to be called a true-blue Tory. With him were Maxwell Raison and Sydney, later Lord Jacobson. The former was the father of the present Tory politician, Timothy and founder of New Scientist and New Society. The latter became head of the IPC magazine and newspaper group and whose son Colin is now the present picture editor of The Independent.

This miscellaneous bunch had only one thing in common: they were in the thrall of a mad Hungarian Stefan Lorant. Mad is to be understood in its nicest sense; eccentric. egotistical but touched with genius. His story is worth a talk on its own but, suffice to say, he had been the editor of the Munich Illustrated weekly and had been imprisoned by the Nazis, released and then he escaped to Britain. His flamboyant sense of journalism shaped Picture Post into the major anti-Hitler voice in Fleet Street at a time when not only The Times but the rest of the Street were advising appeasement. Thus Picture Post became a crusading magazine and many other crusades were to follow.

Lorant was not a photographer but a picture editor of incredible memory and vision. He needed photographers who could work with him and who understood his idea of a picture story. Not surprisingly he used three fellow refugees, all born in Germany and with whom he had worked in Munich. It was these three and Stefan who created that visual sensation that was to influence picture journalism worldwide. To give but one example, the teenage Leonard McCoombe devoured every issue with the sole ambition of becoming a Picture Post photographer. He became their youngest and through his magnificent sets of pictures of Berlin after the war went on to Life. It is to him rather than Gene Smith that we owe the concept of the photo-essay (Ref 5).

The three in the foreground of Picture Post in the early days were Felix Man (Ref 6), Kurt Hutton (Ref 7) and Tim Gidal (Ref 8). Three photographers of widely differing personalities but with this common Munich and Berlin experience. Perhaps it is true to say that their similarities were more important than their differences, even though the latter gave pace and flavour to the magazine. Stefan Lorant at a symposium on Picture Post was asked how he could prove a particular point. His simple answer was “look at the pictures”. Not only is the answer worth remembering for historians but it is worth adding the corollary that if it doesn’t show in the pictures, it doesn’t exist.

BRITISH LANDSCAPE MASTERS

My final example could very well be introduced by the injunction to ‘look at the pictures’. They are the photographers who must be grouped as the modern British landscape photographers although they would probably hate to be so grouped. The group would include Fay Godwin, Paul Hill, Ray Moore and Bill Brandt and even in a smaller way Kurt Hutton. Ray Moore (Ref 9) and Roger Mayne (Ref 10) have both written in V&A catalogues about the influence on them of Hugo van Wadenoyen and countless thousands of others, including myself, will have learnt from him through his Focal Press books. His trade was portraiture and he wrote informatively about it but just after the war appeared ‘Wayside Snapshots’. Unfortunately his good photographic print quality was lost by poor book printing. Hugo was also the principal author in the incredibly cheap series of booklets which included ‘All about Landscapes’ and, with what would now be called urban landscapes, ‘All about Pictures in Town’. These were seminal works in the 40’s but many of the illustrations came from pre-war.

Hugo’s influence was even greater round his home in Cheltenham. He lectured well and frequently to local camera clubs and, as Roger Mayne has recorded, for some years he judged exhibitions and helped invigorate the Combined Societies Exhibitions. There are still photographers around with reminiscences of him (and I would like to hear from more) for his personality made him easily accessible to photographers willing to learn. Perhaps it is appropriate to finish with him because although he earned his FRPS just after World War 1 he never stopped learning and became a seminal figure after World War 11.

The title of this talk uses the words Contemporary Creativity. Creativity belongs to every age but for contemporary people as I have tried to show it has more substance, more importance, if it arises out of a consciousness of photographic history.

References…

Ref. 1 New Light on the Beato Brothers by Colin Osman. B.J.P 16.10.87.

Ref. 2 Thomas Child (1841-1898) Photographer of Peking by Colin Osman. Photo- Historian Supplement 86A Autumn 1989

Ref. 3 William Simpson; Autobiography. London 1904.

Ref. 4 50 years of Picture Magazines. Creative Camera double issue July/August (Nos 211/212). Edited by Colin Osman

Ref. 5 Life Photographers: Their Careers and Favourite Pictures by Stanley Rayfield. New York 1957.

Ref. 6 Man with Camera: Autobiography. Felix Man. Seeker and Warburg 1983.

Ref 7 Kurt Hutton by Colin Osman. Creative Camera Year Book 1975.

Ref 8 Tim Gidal in the Forties by Nigel Trow. London 1981.

Ref. 9 Murmurs at Every Turn: The Photographs of Raymond Moore by Mark Haworth-Booth. Travelling Light 1981.

Ref 10 The Photographs of Roger Mayne by Mark Haworth-Booth. V&A Museum 1986.