I was initially prompted to add this section on Tony Ray-Jones by two almost coincident articles published about him in 2004. The first was in Source magazine, where Ian Walker conveyed a fascinating tale of detection and discovery entitled ‘Summer of Love’ based around one photograph by Ray-Jones, reproduced on the left.

The second article, by Liz Jobey in the Guardian Weekend magazine (Oct 2004) and entitled ‘The English Seen’ , featured the same photograph leading into a brief biography and synopsis of Ray-Jones’s work and influences linked to the major show of his work held in the UK in late 2004.

Since then, these pages about him have attracted thousands of visits from all over the world, testimony to the enduring legacy of the man and his work.

“The number of socially committed photographers is practically nil. Reason being – it’s not financially rewarding and secondly it’s very hard, tedious and time-consuming. This is partly why I can’t consider photography in general as an art but I believe at its best it can be.

Surely the most vital and important use of the camera is a personal tool, especially social. Its importance lies in this field because of its size, format, mechanics, etc. To pursue solely texture, line and form seems to me to be fruitless, as much can be accomplished by pencil and brush.”

Tony Ray-Jones, personal letter, May 25th 1965

These two page reproductions, from Creative Camera, April 1969, accompanied an article about the first exhibition of photography to be held at London’s Institute of Contemporary Arts in The Mall.

Tony Ray-Jones featured in this show, along with other one-person exhibits by Don McCullin, Dorothea Bohm and Vincenzo Ragazzini.

Over the same period, Henri Cartier-Bresson, whom Ray-Jones admired more than any other living photographer, had his first one-man exhibition at the Victoria & Albert Museum in London. Even in 1969, Cartier-Bresson was described as ‘…one of the finest and most influential photographers of all time’.

At around the same time as the articles mentioned above were published, Richard Avedon died. Although Ray-Jones later claimed to despise commercial photography, he studied in Avedon’s studio in New York in the early 1960s. Ray-Jones also worked with Bill Jay on Creative Camera magazine (then called Creative Camera Owner) in 1968 and famously said to Jay at the time: “Your magazine’s shit, but I can see you’re trying. You just don’t know enough, so I am here to help you.” He was offered a job and worked on the magazine during 1969 as ‘Consultant’.

In a previous issue, Bill Jay had written this about Ray-Jones to accompany a single image from the British Council’s ‘Personal Views’ touring exhibition: “It is difficult to find a more fiercely committed photographer than Tony Ray-Jones. He despises ‘phoney-baloney’ pictures, those that inflate the photographer’s ego at the expense of truth and integrity.”

Ray-Jones’s style of photography is far removed from my own, but I have been completely in awe of the body of work he left behind since I first discovered it in the mid-1970s. Before I new of his existence Tony Ray-Jones had died of a rare form of leukæmia on March 13th, 1972, aged just 30. He never saw his first book of photographs published.

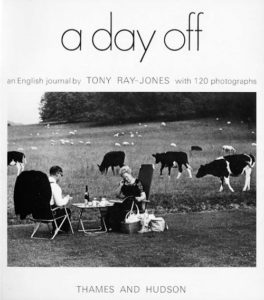

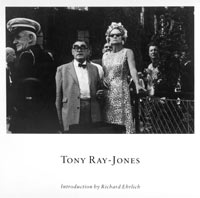

My well-thumbed copy of A Day Off: an English journal (Thames & Hudson), published after his death, is a book I have treasured since 1975. I return to it when I need reassurance of how the essence of photography can be distilled by a visionary artist. Ray-Jones is still ranked highly amongst the best of British photographers and considered by many a genius behind a camera. There are two other major books on Ray-Jones’ work, listed here. All are still available but in some cases at a high price. A brief obituary, written by John Benton-Harris, was published in Creative Camera in June 1972.

But by many accounts this genius was offset by a somewhat abrasive and arrogant personality that, over time, alienated many friends and would-be supporters. Although a likable person, he hardly had a good word to say about other photographers, with the exception of Henri Cartier-Bresson, whom he revered, and Bill Brandt. His pictures are certainly about ‘decisive moments’ just as much as Cartier-Bresson’s, and he had the keen sense of drama and tension that comes through in Brandt’s work. But Ray-Jones’s moments are quirky and slightly off-kilter, almost bordering on surrealist in their viewpoint. He was a great pre-visionist. He knew the components he needed to make a picture that would satisfy him even if he had no firm idea how those components would come together in the final composition. His contact sheets show that he knew when the possibilities of a chosen scene were exhausted and at this point he would often move to a new subject.His notebooks were full of lists, plans and ideas for pictures in certain locations, with certain desirable characters and elements described in advance. Sadly, he was not around long enough to mature into “the English Cartier-Bresson“, but those moments when his complex cast of performers and props fell into place and he captured their fleeting tableau vivant in a fraction of a second, mark his genius and his art.

One of his lists, headed ‘APPROACH’ was reproduced in Richard Ehrlich’s 1990 book:

- BE MORE AGGRESSIVE

- GET MORE INVOLVED (TALK TO PEOPLE)

- STAY WITH THE SUBJECT MATTER (BE PATIENT)

- TAKE SIMPLER PICTURES

- SEE IF EVERYTHING IN BACKGROUND RELATES TO SUBJECT MATTER

- VARY COMPOSITIONS AND ANGLES MORE

- BE MORE AWARE OF COMPOSITION

- DON’T TAKE BORING PICTURES

- GET IN CLOSER (USE 50mm LENS {or LESS, hard to make out in notes})

- WATCH CAMERA SHAKE (shoot 250sec or above)

- DON’T SHOOT TOO MUCH

- NOT ALL AT EYE LEVEL

Everything mentioned here still holds good for any serious photographer in this genre today.

He was inspired by the photography he found in America during his stay there in the first half of the 1960s, the work of those such as Robert Frank, Gary Winogrand and Lee Friedlander. He took something of their style and approach and made it his own, taking the English way of life as his subject and interpreting it in a very English way. He was not the only UK photographer to produce this kind of work – Roger Mayne, David Hurn, Ian Berry, Patrick Ward and Don McCullin were all active around the same time and similarly ground-breaking in their approach.

Tony Ray-Jones was not solely responsible for the development of this style of documentary and street photography in Britain, neither was he the first photographer to discover the ‘American way’ and introduce it to our shores. In his typical fashion, he named Bill Brandt as “..the only photographer to produce an honest and personal document of the English people.”

In the words of John Szarkowski however: “…the surprising thing about Ray-Jones was that he had a different idea of what subject matter was possible for serious photography. It did not have to be heroic or poetic in any overt sense: it could be on the surface as tedious or as bland as our real tedious and bland lives usually are, and the photographs might still be compelling.”

He had a knack of choosing scenes where the ordinary suddenly became bizarre – almost surreal – as the various unwitting players in his tableau fell into place. His genius was in recognising likely scenes and capturing the moment when the ‘right’ juxtapositions took place. This new approach to subject matter, perhaps an English form of ‘Neue Sachlichkeit’, went on to inspire the likes of UK photographers Martin Parr, Homer Sykes, Paddy Summerfield and John Benton-Harris – an US anglophile who was a close friend of Ray-Jones and who also studied under Alexey Brodovitch at the Design Lab in New York. Of Brodovitch, Ray-Jones once said “…(he) encouraged me and gave me tremendous inspiration.” (Creative Camera, Oct. 1968)

You can read some of Brodovitch’s writing in my ‘Ephemera‘ section.

We owe a debt of gratitude to Brodovitch – and maybe in a lateral way to Avedon, in whose studio the enormously popular and successful Design Lab was run – and to all the others who encouraged a young, arrogant but driven Englishman to create, during his short lifetime, a lasting impression on our photographic history and leave behind a set of images of England that are still classed as masterful 40+ years on.

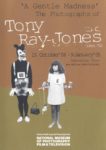

A major retrospective of his work was shown at the National Media Museum in Bradford, UK, 2004/2005. Although many of the pictures shown were well-known, there were also previously unpublished examples of his work. It was particularly interesting to see more of the colour material produced for the Sunday Times Magazine, further evidence (if any more was needed) that his already important contribution to British photographic art and history was just beginning at the time of his death.

More recently, a fascinating compilation of his published and unpublished photographs was held at the London Science Museum Media Space (2013-2014). Curated by Martin Parr, it brought together Parr’s own work from ‘The Non-Conformists’ with new images drawn from the Ray-Jones negative archive at the National Media Museum, selected by Parr. Seen alongside the more well-known images originally chosen by Ray-Jones himself, this new collection was enlightening and contained some interesting work, but none really achieved quite the same resonance as the original selection, although some came very close.

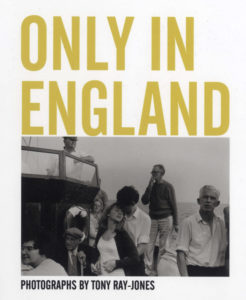

To accompany the show, a new book was published entitled ‘Only in England‘, a worthy addition to the library of work by this remarkable photographer. Also published in 2014 was a collection of Ray-Jones colour work from his stay in the U.S. – American Colour.

This site’s review of the exhibition ‘Only in England‘ appears here.

In 1994, a commemorative Green Plaque was placed on the house that Ray-Jones lived in at 102 Gloucester Place, London, by Westminster Council.

© Text copyright Roy Hammans, except where stated. February 2005.