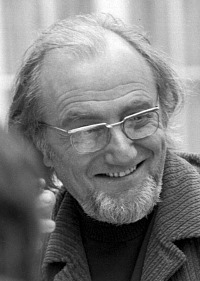

Raymond Moore (1920-1987) has been gone a long time.

Yet this important and influential British photographer, considered a key player in the development of photographic practice in the UK, is not just gone but also almost forgotten. Photo-historians and academics do their best to bring his work to the attention of students; curators and gallery owners would love to be able to get their hands on his prints to exhibit or sell; publishers often wish to include his work in books on the history of photography. But, due to a still unresolved legal issue following his death, his archive of images languishes in some vault, hopefully well-protected, while his achievements and the importance of his contribution fade from memory.

When I searched the web for information on Moore back in 2007, there was nothing except a Wikipedia entry. There is more now and sources are linked throughout the articles here. This section of the site is an attempt to provide some background and information on this much-neglected photographer.

Confronted by the myriad relationships between objects in the visual world, I am impelled to choose or select those happenings that most accurately reflect a state of being at that one moment in time. This choice is governed by an instinctive awareness of the medium’s essential power of translating and recreating in photographic terms. A new world is magically presented in the form of marks made by the optical-chemical process, related to the world of everyday visual contact and yet quite apart from it. From this map of experience, hopefully something of value may be revealed. – Raymond Moore

Like many other photographers, Raymond Moore started his artistic career as a painter. He was born in Wallasey, Cheshire, in 1920, and after studying at Wallasey College of Art he won an exhibition scholarship to the Royal College of Art at the age of 27. After graduation, he gradually came to realise that photography offered him a more appropriate medium for his art than painting. In that period between 1950 and 1970 British independent photography was under-nourished and lacking support. Some individuals rose above these constraints and captured the public’s attention, but the underlying theme of their work was usually one of fashion, photojournalism or documentary in the purest of senses.

Allonby, West Cumbrian Coast, England.

The ‘Picture Post‘ tradition was still extremely strong in the UK – Brandt worked for that magazine alongside many other historic names. Bailey’s reputation in fashion was achieved largely through the medium of magazine publication. McCullin’s likewise – with the added ingredients of personal risk and the horrors of war. Even Edwin Smith’s work relied on the relatively buoyant market for ‘coffee table’ books. But by 1970 people like Tony Ray-Jones had started to set a completely new agenda, Creative Camera magazine had evolved into the main conduit for ‘serious’ photography in the UK, and Raymond Moore had a one-man show…in George Eastman House, Rochester, USA.

Why in America? – because that country had already woken up to style of photography that he was exploring and was willing to embrace it. To be fair, Moore had already been the first living British photographer to have an exhibition funded and promoted by the Arts Council (the Welsh Arts Council to be precise) back in 1968, and he was already quite well known amongst the photo-literati in Britain and America. In 1970 Moore had worked for a short while with Minor White at M.I.T. in the US. Moore’s style has some affinity with that of White and they shared a mutual interest in Zen philosophy. Although it would appear that their respective styles of photography had evolved independently, perhaps a Zen perspective would be that they were both part of the same inseparable whole.

Moore photographed things that few others did. His work is difficult to categorise under any heading; it appears somewhat journalistic in its execution and is certainly a form of documentary. But it is concerned not with the subject of the photograph itself but rather with ‘the no-mans land between the real and the fantasy’ as Moore himself put it.

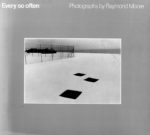

It is a type of photography that performs best for the viewer in the formal surroundings of a gallery, or through the medium of a well-produced book. Publications or exhibitions of such photography were almost non-existent at this time; collectors of such work equally scarce. Moore had his first one-man show in London in 1959, another in 1962 and two in Wales in 1966. His photographic vision was continuously evolving – and continued to evolve up to and beyond his major retrospective at London’s Hayward Gallery in 1981.

This was only the second exhibition accorded to a British photographer at the prestigious London venue – the first had been Bill Brandt in 1970. Although Brandt was well known by anyone with an interest in photographic art, Moore remained primarily a photographer’s photographer. His work was certainly not as accessible as that of Brandt. There were no portraits of famous people, no grand scenic landscape, no nudes, no ‘period pieces’. Moore created photographs of the commonplace, but in a way that suggested there was something uncommonly strange about it – “the magic that lies beneath the surface of things“, in Moore’s own words again.

Moore explored isolated and marginal areas in much of his work – ‘the edge of civilisation’ he called it. Not that these areas were geographically distant, often they were very close to where he happened to live at the time. During his years at Watford he lived with the painter Ray Howard-Jones and was considerably influenced by her work. Some say that he produced his best pictures during his ‘London years’, the later work produced after the move to Nottingham and then Cumbria lacking the ‘concentration on detail‘ of the earlier period, as Helmut Gernsheim put it.

Moore remained a prolific artist and dedicated teacher throughout his life. His tutelage of photography workshops – notably at the Photographers’ Place run by Paul Hill in Derbysire during the 1970s, 80s and 90s- was almost legendary within the British photographic community. No one that attended these ever forgot the debt they owed to ‘Ray’ and many notable photographers were inspired by his teaching – either in these workshops or through his teaching at Watford or Trent. Although a generation removed from many of these students his outlook on, and dedication to, the medium of photography placed him on exactly the same plane as his enthusiastic acolytes. Regrettably, I never made it to a Ray Moore workshop and never got it together to invite him to run a workshop at the Cambridge Darkroom before he left us. My conversations with those that did meet and work with him make me realise what I missed.

His name still crops up in articles or references to the ‘rebirth of British photography’ in the latter half of the last century and he is often the subject of college dissertations and theses and I get many enquiries from students researching the man. His work is still held up as an example of a type of imagery that helped break down the boundaries between traditional photography and ‘fine art’, smoothing the way for a new generation of artists to use the medium freely in whatever way they felt appropriate. Raymond Moore worked with landscape and objects the way that Tony Ray-Jones worked with people – he found a new way to make visible through photography that which he saw and perhaps others didn’t. His photographs may not be to all tastes but they are an expression of ‘self’ and of one man’s vision (although he hated the term ‘self-expression’).

Some indication of his standing amongst ‘those in the know’ was the production of a BBC film about him in 1983. This has been loaded onto YouTube and is available to view here.

Perhaps there will be a ‘Raymond Moore Revival’ soon – he’s about due for one, just as Tony Ray-Jones has been rediscovered by a whole new generation. This can only be a good thing. His work is not seen in many places these days, his books are out of print, and will the Raymond Moore archive ever see the light of day?

This archive comprises of all of Moore’s negatives, contact sheets, around 700-1000 prints, drawings, correspondence, and publications; it’s value was estimated at £440,000 in 1990 – as ever, all art has to have a price attached these days…(source: The Guardian, Monday September 17, 1990)

© Creative Commons License – Roy Hammans, 2008 (updated 2020)