Edwin Smith’s wife and immensely important in his life and work.

It is apt, and perhaps inevitable, that Olive Cook’s first book was Cambridgeshire: Aspects of a County, for she was born, brought up and educated in Cambridge. In Cambridgeshire she wrote, ‘It is not easy to give an impression of a place to which one has never been a stranger’; and ‘Every native of the town and all the men and women who have spent three years of their lives among those images of splendour and repose must forever cherish memories of Cambridge.‘ Olive’s parents and grandparents were Cambridge people too.=

Arthur Hugh Cook, born in 1886, was the sixth of the seven children of George and Sarah Cook. In 1901 George Cook is described as a plasterer living at 35 Montague Road, a solid bay fronted semi-detached house in the fashionable Defreville Estate that was developed in the 1890s. He was probably a small speculative builder of the sort more common then; and plastering, including creating fashionable decorative molding, was a considerable craft skill. Arthur, 15 in 1901 appears still to have been at school; he started work at the University Library in 1903.

Kate Webb was born in 1883, the oldest of the four children of George R Webb and Susannah Webb. In 1901 the family was living at 9 Upper Gwydir Street, a very modest Victorian terraced house in a distinctly poorer quarter of the City. George was a furniture dealer’s assistant. Kate, 18 in 1901 was a dressmaker, possibly then, or later, for Robert Sayle (subsequently the John Lewis Partnership store in Cambridge).

Arthur Hugh and Kate were married by 1911 and early that year they moved into The Maisonette, 43 Garden Walk, an attractuive little bay fronted end-terrace house built by George Cook on land he had purchased in 1908. Olive Muriel Cook was born in here on 20th February 1912.

Arthur and Kate Cook moved to a more substantial semi-detached house at 8 Leys Road in 1922-23; and on to a detached house at 24 Luard Road in 1934-35. Arthur retired from the University Library after 53 years service in September 1956 and in December was made an honorary Master of Arts of the University. The Cooks were then living in Melbourn, Cambs.

Olive was educated at the Perse School, then the premier girls’ grammar school in Cambridge. In 1929 she was awarded a Certificate au Grand Concours Special by the Societe Nationale de Professeurs de Francais en Angleterre. She won a scholarship to Newnham College (founded 1871) in 1931, where she lived in Sidwick Hall, and took the Modern and Medieval Language Tripos (French and German). She visited Germany several times, experiences which later stood her in good stead working on books on German architecture. Olive ‘graduated’ with 2nd Class Honours (II2) in 1934 – it was not graduating in the modern sense as women were not full members of the University until 1948, so she would have had a titular degree certificate. She was awarded her MA in June 1942. As an undergraduate at Cambridge Olive was one of a small, privileged group of women. In the early 1930s there were only some 500-600 women undergraduates, around 10% of students; today there are around 5,700 women making up almost 50%.

Olive’s contemporaries at Newnham College included Elisabeth Ayrton (cookery writer, 1910-91), Jacquetta Hawkes (archaeologist, 1910-96), Catherine Storr (children’s author, 1913-2001), Dorothy Hodgkin (Nobel Prize winning chemist, 1910-94) and Baroness Nancy Seear (Liberal peer, 1913-97).

On completing her degree she spent some time studying art under Cedric Morris at the East Anglian School of Painting, established at Dedham in 1937.

Her first job was as an art reader and editor for Chatto and Windus, followed by a stint as supervisor of publications at the National Gallery (1936-1947), where she worked with Kenneth Clark. She met and became friends with official war artists, including Eric Ravilious, Thomas Hennell and Stanley Spencer. From 1940 to 1945 she was an air raid warden in Hampstead, London.

In 1940 with the familiar British landscape under triple attack from Germany, rapid urban development and major changes in farming practice, the Ministry of Labour and the Pilgrim Trust set up the Recording Britain project. The project commissioned artists to record the changing face of the countryside before it was too late. The artists commissioned were those ‘who could not be concerned with the record of war and were going through bad times’. Recording Britain – A Pictorial Domesday of Pre War Britain (1990) notes that: ‘The result was less a record of change than a tribute to continuity, a celebration of “Englishness”’; and ‘At its core is the enduring myth of idyllic and redemptive rural life’.

Olive was one of the artists commissioned for the project and two of her romantic watercolours are held by the Victoria and Albert Museum: ‘Backyard of the Abbey Arms Hotel, Festiniog, N. Wales(September 1943)’ and ‘Disused Tin Mine, St Agnes, Cornwall’ (no date).

Commenting of the mine painting, Recording Britain says, ‘Cook is better known as a writer than as a painter, but this rigorous and character image, very much in the neo-romantic manner, demonstrates her considerable abilities in the medium.’

Commenting on the project in Recording Britain, David Mellor refers to a strand of the work in which artists explored Victorian shop signs and other vernacular motifs. He writes:

“The same paradigm of a vernacular culture was explored by Olive Cook, a ‘Recording Britain’ artist who also worked at the National Gallery. Olive Cook and Edwin Smith’s contribution to the annual Saturday Book, beginning in 1941-2, mapped British Design and popular taste in terms of etched pub glass, Victorian religious mottoes, Edwardian shop windows and dilapidated mills. This lexicon is suggestive of sub-group tastes which prevailed among Enid Marx [1902-98], Barbara Jones [1912-78], Olive Cook and Edwin Smith. They particularly favoured Louis Meier’s antique shop in Cecil Court and the second-hand booksellers of Farringdon Road, but the pursuit of the vernacular was competitive; if one of the group saw something piquant in a junk-shop ‘you couldn’t tell Barbara [Jones] or she’d be there ahead of you’ ”

In 1948 she left the National Gallery to devote herself to her own writing and painting. In March of that year she gave a lecture on ‘The Painting of English Landscape’ at Jesus College. Phrases from that lecture reflected her view of a romantic England at the mercy of modernity: ‘[John] Constable combines to a degree unsurpassed the freshness of the actual scene with all the essentials of architecture, tone, volume, mass….his landscapes are informed with the feeling of an almost mystical union between nature and the human soul….Constable was fortunately spared the pain of witnessing the growth of industrialism…Mean towns were springing up as suddenly as mushrooms overnight, joyless and pregnant with decay and destruction.’

Her works have been shown in many exhibitions, including The London Group (est. 1913), The Women’s International Art Club (1901-78), Leicester Galleries, Arcade Gallery (London), Ferens Art Gallery (Hull) and the Fry Art Gallery (Saffron Walden). She was a prize winner in an Italian Government painting competition, Premio Agrigento, in 1952; her portrait of Edwin Smith (c. 1955) hangs in the National Portrait Gallery. In the 1960s Olive was a visiting tutor in painting at Denman College (the Women’s Institute’s own Residential Adult Education College), near Oxford. In 1985, along with Iris Weaver, she was instrumental in establishing the Fry Art Gallery in Saffron Walden, exhibiting her own paintings and writing biographical sketches of the artists of the North West Essex Collection deposited there.

Olive Cook is not easy to pigeon-hole as a writer, but principally she was a critic and commentator on art, architecture and topography, with only modest forays into the realm of fiction. She also wrote expertly on early cinema in the seminal work Movement in Two Dimensions (1963).

She published Suffolk (in the Vision of England series) (1948), Cambridgeshire: Aspects of a County (1953), The Playbook Library, stories with nursery friezes designed by George Adams (1954) and Breckland (1956). Olive’s allegorical story, Ardna Gashel, was published by the Golden Head Press in 1970. Throughout her life she contributed to Matrix, an annual magazine on typography, printing and books generally published by the Whittington Press. She also wrote forewords, afterwords and notes to many books on architecture and heritage, and translated, adapted and arranged several books on German buildings.

During the early 1940s, she met Edwin Smith, whom she married in 1954; they lived in Hampstead where they had a large circle of artist and writer friends. From 1944 she and Smith started to write and illustrate articles for The Saturday Book edited by Leonard Russell, to which they both contributed annually until Edwin’s death. 1954 saw the publication of English Cottages and Farmhouses, for which Olive wrote the text to accompany photographs by Smith. More joint books followed, including English Abbeys and Priories, British Churches, The Wonders of Italy and The English House Through Seven Centuries.

Edwin and Olive moved to Saffron Walden in 1962, where Olive pursued her passion for the preservation of the countryside. Her book The Stansted Affair (1967) presenting the case against the development of a third London airport; and in 1969 she wrote Anstey, for the Nuthampstead Preservation Association in opposition to a proposed site for the airport. They purchased the Coach House, Saffron Walden, in 1967 and remodelled and decorated it in the romantic image of an earlier time. She was a founder member and dedicated supporter of The Fry Art Gallery, Saffron Walden, which houses a fascinating collection of varied work by artists local to the area, including some by Olive and Edwin.

The premature death of Edwin in 1971 devastated Olive. However, a woman of great spirit and forceful character, she worked tirelessly to further the reputation of her husband, producing Edwin Smith: Photographs 1935-1971 (1984) and continually promoting his work through exhibitions and in books of others, such as Lucy Archer’s Architecture in Britain and Ireland 600-1500 (1999).

Olive also continued her independent work. She wrote: the libretto for The Slit Goose Feather (1978) composed by Christopher Brown; Tryphema Pruss (1999), illustrated by Walter Hoyle; and the introduction for Hoyle’s To Sicily with Edward Bawden (1998).

It is the extensive body of publications over nearly sixty years that establishes Olive’s reputation as a perceptive and stylish writer on places, art and architecture. She varied her style to suit the subject.

In The Saturday Book for 1946 she brings life to the potentially dull subject of painting the horse:

“The miraculous rendering of the stance and weight of the White Mare [by Stubbs] is the result of intense and loving study, but it is an astonishingly objective portrait compared with the romantic interpretations of those other horse worshippers Delacroix and Gericault, whose turbulent spirits look out from the rolling eyes if the quivering storm-stricken creatures they paint with such mastery.”

Writing of her home town in Cambridgeshire she captures the sense of place of Cambridge in the late 1940s and early 1950s:

“Cambridge puts on a different face with term and vacation.When the undergraduates are in residence the narrow streets, already on market days full to overflowing with the swollen population, are still further congested with hurrying black-gowned figures and with hundreds of bicycles dangerously slipping in and out of the traffic or flung in piles at college gates, against the railings of Holy Trinity Church, outside Boots’, beside Heffer’s in Petty Cury and wherever there is wall space. Even Market Hill (a hill in name only), where canvas-covered booths display fruit and vegetables, flowers, garments, flashy jewellery, china and old junk in the shadow of Great St Mary’s, is invaded by black gowns.”

Turing to a later description of a photograph by Edwin Smith, her style is more florid, but does justice to his work:

“The light was marvellously expressive, a dream-like twilight which revealed every tile and plant and enhanced the strange reality of an incredibly romantic crucked and crooked manor house juxtaposed to prim Georgian cottages and shallow gardens enclosed by fat, closely cut hedges or white railings. This chance of light, moment and mood produced some magical photographs.”

By comparison, in Ardna Gashel Olive is overcome by her own polemic against modern art and manages to be overblown and leaden at the same time:

“Unfortunately however, the lavish praise, the incessant attention and the great privileges accorded to these artist-rulers were in the end their undoing. They became, I regret to say, swollen headed. The symptoms of the sad change first became apparent in the work of the celebrated woman painter Edain. She suddenly began to produce the most ill-natured, distorted caricatures of her companions and of the kings who had so generously entertained her at their courts. But worse was to come. Soon Edain no longer cared whether the images on her canvasses conveyed anything at all to others: she, who had heralded Raphael in the perfection of her technique and Rembrandt in the disciplined expression of her passions, now cast aside all the established elements of pictorial composition…”

Olive Cook had an enormous capacity for friendship, as the hundreds of cards in her papers attest, and although she had no children herself, she was clearly a great favourite with those of her many friends. There was a special affinity with the photographer James Ravilious (1939-1999, son of Eric Ravilious). The English Eye (2007), a book of his work records: ‘Olive Cook often looked after James Ravilious during his mother’s illness, and remained a close friend, “almost a godmother” after Tirzah Garwood’s death [1951]’.

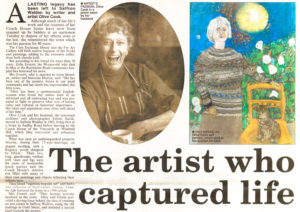

Olive died on 2 May 2002, aged 90. Newnham College held a memorial celebration for Olive’s life in October 2002. An article about her in the Cambridge Evening News, published in December 2002 is shown on the left. Linked here is a PDF downloadable version of this Cambridge Evening News article on Olive Cook.

Olive Cook was a remarkable woman. She was passionate, intelligent, forthright, dedicated and disciplined, and unless this sounds unduly serious, enormously interesting and fun to be with. She was also a traditionalist, not to say conservative, and a self-confessed elitist.

In notes for a lecture at Denman College in the 1960s she dismisses Jackson Pollock, suggesting that some people may find release in his scrawls, but it ‘has nothing whatsoever to do with the art of painting as we have always known it. It is a different sort of activity and should be recognised as such.’ She concluded the lecture with an appeal to her audience: ‘It is not from the so-called progressive painters of our day with their complete rejection of all the technique and tradition built up over 500 years that a new movement will derive nourishment, but from the enthusiasm and conviction of our amateurs.’

Her allegory Ardna Gashel develops this in a dismissal of all that the modern world had to offer in art and architecture. Thirty years later she was still railing against the modern world against the modern world: ‘in our own time the word “new” signifies a comp-late break with tradition. The vivid sense of continuity….no longer cushions the shock of the new. The desire for the new is the most telling indication of the post culture in which we now live.’ (Matrix 20, Winter 2000) The practical sincerity of her love of the countryside is reflected in the part she took in campaigns against the Third London Airport. Her views were extremely traditional and her outlook embedded in a romantic past. However, this should not blind us to the real affinity she had with English architecture and landscape, an affinity she was able to convey in her distinctive descriptive literary style which, if occasionally managing to be the unlikely combination of florid and academic, is always eloquent and readable. She did not, however, have the same fluency in her small output of fiction.

Her passion for traditional buildings and landscape and her literary skills made her an ideal creative partner for Edwin Smith, a partnership given full rein in their important joint publications. She was also his ideal partner in a personal sense. Strong, organised, earning money through her own work and at least his equal intellectually, she provided the mercurial and often exasperating Edwin with the space, stability and emotional support he needed to do his own work. She may have sacrificed her own career, and almost certainly the motherhood she wanted, to ensure that Smith’s work flourished. She dedicated the remaining 21 years of her life to this. Olive cannot be described as Edwin’s muse, but she does fit in a long tradition of women who influence creative artists. She was no Gala Dali, Elizabeth Siddal nor Charis Weston, but perhaps closer to the supportive Alice Elgar, who did so much to orchestrate the success of Edward Elgar. Thus Olive remains to a large extent in Edwin’s shadow. The time is right for a proper appraisal of her achievements.

The Olive Cook Papers, a collection of the personal and business papers of Olive Cook and Edwin Smith were donated to Newnham College by the executors of her estate in 2003. Cook inherited Smith’s estate on his death and towards the end of her life deposited his photograph collection at the Royal Institute of British Architects (RIBA) along with their personal letters to each other.

The Olive Cook Award for a short story was established in 2004 as a result of a bequest made by Olive. It is given biannually and administered by the Society of Authors.

Brian Human

18th February 2010