He could never understand lack of enthusiasm, in students for example. He drove himself as if he sensed there was little time to lose. Benton-Harris says he was an amazingly good hustler, and other photographers have remarked that he had a knack for reminding them what it was all about. He had a charismatic power to instill enthusiasm and he could have become a remarkably good teacher. The fierce criticism, the radical element in him, was balanced by a natural unaffected charm, a ripe sense of humour, real warmth. This is how he struck Jacques Lartigue, a photographer for whom he had the greatest affection and regard. Lartigue writes: ‘At Opio, in 1970, I had the surprise one day of a charming visit, that of Tony Ray-Jones. Intelligent, young, free “et fantaisiste” (Translator’s note: The nearest one can get to this delightful word in English is “expressing gently humorous tolerance, or whimsical”), he travelled in a dormobile. Without knowing him I sensed at once that he must have talent.

Several months later, in a gallery at that time directed by my friend Pierre de Fenoyl, I was able to see his first exhibition in Paris and I am always delighted when I meet real talent. His was like himself: young, intelligent, free and whimsical with, in addition, a very sound technique and a vision of fire that was full of humour, truth and a sense of poetry in certain subjects. I am very certain then that in spite of his presence for too short a time on earth, his work will leave behind a very profound memory.‘

Tony also thought highly of the work of Paul Strand and, for instance, particularly liked the whole presentation of his Mexican Portfolio.

Paul Strand first saw Ray-Jones’s work in Album 3 (Ed. Note: Bill Jay’s short-lived journal).

‘In its all too brief existence Album brought forward memorable works of both known photogra- phers, past and present and not less importantly gave its pages as well to photography by new developing artists. ‘Among the latter, I found the photographs of Tony Ray-Jones very outstanding. In them I find that rather rare concurrence when an artist clearly attaining mastery of his medium, also develops a remarkable way of looking at the life around him, with warmth and understanding. His vision of people as they live in the neighbouring worlds of reality, is comprehensive and complex. Such photographs as “Durham”, “Broadstairs” and “Ramsgate” among others, show a remarkable formal organization, the consistent ability of the photographer to seize images constantly in change and movement, in which however everything he includes in the picture is and unified as a true work of art must be. To my mind “Ramsgate” is a masterpiece of this very inclusive seeing in which the photographed reality, never sighted, is fully alive in every part and as a complete whole.

A young man who had advanced so far along the difficult road of so significant a marriage of form and content is rare today in any medium. The tragic death of Tony Ray-Jones who was working in the great tradition which began with D. 0. Hill, is a real loss to the art of photography in Great Britain and to people everywhere.’

The pictures that he made on his first visit to America he regarded later as merely isolated sketches. He came back to Britain ‘with a foreigner’s outlook, as well as that of a native‘. He now felt that apart from Bill Brandt, England was unexplored from a non-commercial point of view. He turned with a fresh eye to two related sides of English life: holidaying at the seaside and old customs and traditions. ‘Both the Seaside and Old Customs present an opportunity for people to gather, to interact with each other and their environment and thereby to reveal something of themselves.‘

What was that something? It had to do with humour and sadness, and with the gentle madness that overtakes the British when they feel they can let their hair down and be their true selves. This oddity, this eccentricity, was capable of being set down by the camera. ‘Photography can be a mirror and reflect life as it is. But I also think it is possible to walk like Alice through the looking-glass, ·observe the puzzles in one’s head and discover another kind of world with the camera.‘

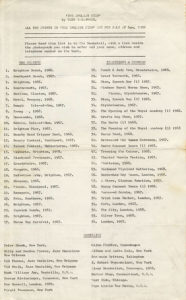

He did not really feel ready for his first exhibition, The English Seen, which was put on at the Institute of Contemporary Arts in London in April 1969, but it contained several of his best pictures. A number of prints included in this show (later seen in Paris and in San Francisco Museum of Art) are held by the Museum of Modern Art in New York and in an archive at the Bibliotheque Nationale in Paris. He took immense trouble to see that these prints should be to his exact liking. As a printer, too, he was demanding. What he sensed, and what he tried to say about the English character is well expressed by George Orwell in a passage about comic seaside postcards. ‘One can learn a good deal about the spirit of England from the comic coloured postcards that you see in the windows of cheap stationers’ shops. These things are a sort of diary upon which the English people have unconsciously recorded themselves. Their old-fashioned outlook, their graded snobberies, their mixture of bawdiness and hypocrisy, their extreme gentleness, their deeply moral attitude to life are all mirrored there.‘ Many of his best photographs seem to be single frames, fluidly and fluently composed, from a film that was running constantly through the gate of his mind. This film was the statement he was burning to make about life. Had he lived he would have turned to film-making even though he is on record as saying, in talking about the film Medium Cool, that the cinema could exhibit an incredible weakness as a means of honest expression and that still photographs could be potent where film fails.