There is, too, a surreal quality about the humour that he loved. For instance Buster Keaton, another of his heroes, has a sequence which particularly amused him. Keaton goes into a bar, takes off his jacket, picks up a piece of chalk, draws a coat hook, and hangs his coat up on it. Surrealism creeps into many of his best photographs. Now Surrealism is basically a curious extension of the ordinary, the bump of surprise that jolts us awake. He had visited the Magritte exhibition at the Tate Gallery but took the trouble to enquire carefully what one of the attendants thought about it. He found out that the things he said were, in fact, deliciously obscure and in a curious way highlighted Magritte’s pictures. Writing in Creative Camera in October 1968 he makes an important statement about his attitude to his photographs of the English, a recurring theme:

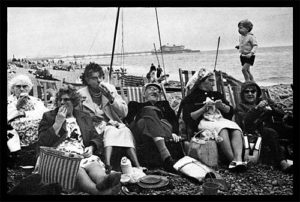

‘My aim is to communicate something of the spirit and the mentality of the English, their habits and their way of life, the ironies that exist in the way they do things, partly through tradition and daily anachronisms in an honest and descriptive manner, the visual aspect being directed by the content. For me there is something very special and rather humorous about the “English way of life” and I wish to record it from my particular point of view before it becomes more Americanized. We are at an important stage in our history, having in a sense just been reduced to an island or defrocked and, as De Gaulle remarked, left naked. Nudity is perhaps more revealing of personality than a heavily clothed figure.‘

Tony sensed the natural eccentricity which has always been a quality of life in this island. He was quality of genuine interest, as opposed to crude curiosity, that is the key to positive contact and relationship. The series on English Eccentrics that he did for the Sunday Times was one of his best sets of pictures for a periodical.

He worried tremendously about layout, the final use to which a photographer’s pictures will be put. This sprang in part from his initial training as a designer at the London College of Printing, his time as a design scholar at Yale, but most of all from his contact with Alexei Brodovitch. Tony studied with Alexei Brodovitch, and with Richard Avedon, at Design Laboratory, New York ’62-’63. He was subsequently appointed Associate Art Director to Brodovitch on Sky magazine in 1964. Tony had an immense affection and regard for Brodovitch whose views on layout, on the study of contact sheets, and on the qualities of a good photograph, he followed and believed. Some of these views were set down by Brodovitch in an article in Photography in 1964.

‘The journalistic photographer must be his own picture editor and art editor. In a commercial job the art director and picture editor should never be a substitute for the photographer’s thinking. When he looks at the ground glass, he should see not only the picture, but four or eight pages. There are two phases in making a picture. The first takes place when the photo is actually shot. The second seeing comes in examining the contacts. It is important to be able to express the pictures which express your viewpoint. It is also important to recognize the accidents which often result in good pictures. ‘What is a good photograph?” I cannot say. A photograph is tied to the time. What is good today may be a cliché tomorrow. The problem of the photographer is to discover his own language, a visual ABC. The picture represents the feelings and the point of view of the intelligence behind the camera. The disease of our age is boredom and a good photographer must combat it. The way to do this is by invention – by surprise.’